Is trickle-down economics an invention of the Left?

Not so much an economic policy, more a focus of hate.

In the week when Liz Truss chose to commemorate the anniversary of her government’s Growth Plan (aka the Kami-Kwasi mini-budget) by giving a speech saying she was right all along, I have been thinking about “trickle-down economics”.

It is said to be a very controversial policy, but I have struggled to find anyone who advocates it. The term “trickle-down” is used almost exclusively by those who wish to describe an economic policy that they despise. One which may not actually exist, except in their imagination.

The “trickle-down” concept is that making the rich richer will lead to a trickling-down of benefits to everyone else. It is not difficult to see why the notion is so offensive to many people. It sounds like a government giving the rich first dibs on new wealth in the hope that the rest of society will pick up the leftovers that the rich chose not to keep for themselves.

There used to be an even more offensive term for it. J K Galbraith wrote about a popular idea from the 1890s called the horse and sparrow theory: "If you feed the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows."

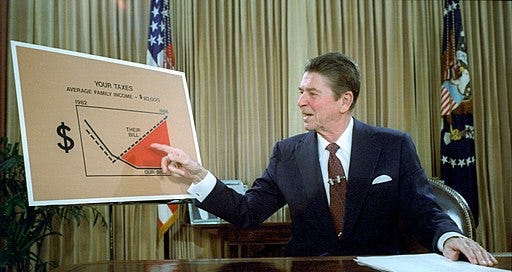

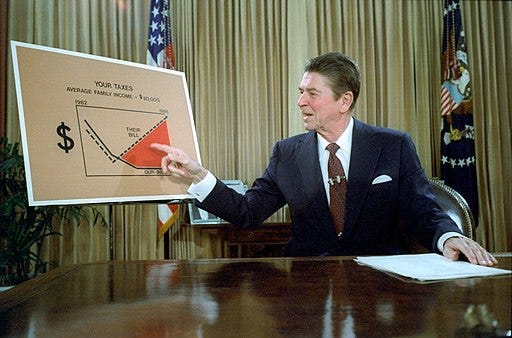

Ronald Regan is often said to have been the trickle-downer-in-chief. But he cannot seriously be described as using tax cuts for the wealthy as the primary driver – let alone the only driver – of his economic policy. Reagan significantly increased government spending (primarily at the Department of Defense), tripling the federal debt during his presidency. Critics of Reaganomics are generally torn between, on the one hand, despising him for pursuing the morally bankrupt (in their eyes) policy of “trickle-down” and, on the other hand, insisting that the economic effects of Reaganomics were because it wasn’t really driven by “trickle-down” after all.

Other sources use the term “trickle-down economics” as an alternative label for “supply-side economics”, a theory in which the supply of goods and services is seen as more important than demand in determining economic growth. The tools of supply-side reform include the promotion of competition (for goods, services and employment), monetary policy (to control inflation) and lower tax rates (in the belief that lower marginal tax rates will induce workers to prefer work over leisure).

Lower taxes for the wealthy play a part in the supply-siders’ armoury. The aim is to encourage investment in business and expenditure on goods. In a world in which that one policy was pursued on its own, in the absence of any other supply-side reforms, one might characterise it as “start at the top and let the benefits work their way through (or trickle their way down).” But to characterise supply-side economics as tax cuts for the wealthy is about as accurate as suggesting that demand-side (or Keynesian) economics is nothing more than increasing taxes on the wealthy.

Let’s apply some common sense. Wealthy people get wealthy by selling things to everyone else. In order to increase that wealth, "everyone else" needs to have enough money to buy in greater quantities. Some governments favour high taxes on the wealthy (in order to finance other policies) and some governments favour low taxes on the wealthy (in order to encourage their economic activity). But no wealthy person with an ounce of sense wants to see the financial ladder pulled up behind them. And I don’t believe any government believes that an economic growth strategy can be built out of tax cuts trickling down.

Everyone remembers Liz Truss’s “mini-budget” (so-called) for the proposed cut in the top rate of income tax – a reduction from 45% to 40%, which the Government said would cost £2 billion and the IFS priced at more like £6 billion. But people tend to forget that she also planned to cut the basic rate of income tax by 1% and National Insurance by 1.25%, at a combined cost of £21 billion. There was also to be a two-year freeze in energy bills at a cost of £60 billion. And so much more besides.

Many people thought Trussonomics was a bad idea. Others thought it was bonkers. (Count me in with the latter.) But it was never designed to trickle. And, whatever her faults, Liz Truss didn’t suggest that it was. As always, it was only those who wanted to score a political point, rather than offer a serious critique, who dribbled out the trickle-down cliché.

This is a bizarre move that will do nothing to support growth, and comes straight from the tired Tory playbook on trickle-down economics which haven't worked for them over the last decade.

Labour's shadow chief secretary to the Treasury, Pat McFadden (23 September 2022)