There is a lot of hot air in this energy crisis

Five myths and misunderstandings about the energy market

Much has been written and spoken about the price of energy in recent months, reaching something of a crescendo a week ago when a new price cap was announced by the energy regulator, Ofgem. But much of the coverage seems to be based on baloney.

The energy industry is complex and not one that I have worked in. My analysis below includes links to the sources I have used. Comments are welcome and can be added in the discussion section beneath this article.

1 Increased gas storage is not the answer

Time and again, critics of the government claim that the crisis is all down to the UK’s decision to cut the level of gas kept in storage. We could, so we are told, have avoided the current high prices by the simple expedient of buying in gas at pre-crisis prices and storing enough of the stuff to get us through the past winter, the coming summer and the winter to follow. (And, presumably, any other seasons after that during which the price spike endures.)

It's true that UK storage of gas is lower than in many other countries. The UK stores 1% of the amount stored by the EU, despite having a population approximately 15% of the size. But does the EU store enough gas to get it through a couple of winters and the intervening summer. No, it doesn’t. What about one winter? Still, no.

The EU’s gas storage in December 2021 was 17.5% of its annual consumption.[1] That’s a matter of weeks’ worth – and not very many weeks in winter. Even if the UK had storage levels that matched the entirety of the EU’s, that still wouldn’t be enough for a single year of UK usage.[2]

These figures shouldn’t come as a surprise. Countries don’t store gas in order to protect themselves against a spike in price. Gas is stored in order to ensure that there is enough gas flowing through the pipes when it is needed – in other words, to manage short-term demand fluctuations, not medium-term (or long-term) price changes.

2 The failure of supply companies is not a failure of regulation

More than half of Britain’s household energy suppliers have gone bust in the past year. Put like that, it sounds like a total disaster and a sign of complete mismanagement by the energy regulator. Sections of the press like to paint it that way. But is it?

The so-called energy “suppliers” are not the companies that deliver energy to our homes. They are simply the companies that we pay so that some other company delivers energy to our homes. If a supplier goes bust, everything just carries on as normal. Not only does the gas and electricity keep flowing, but the regulator automatically allocates the customer to a replacement supplier. I have been in that position: it’s pretty much seamless for the customer.

In London and the East and South East of England, UK Power Networks delivers the electricity, regardless of which supplier the customer actually pays. In other parts of the country, a different company carries out UKPN’s role, but the arrangement is still the same. And so too for gas. It is those companies – known as “distribution” companies – who carry on delivering to households even if the “supplier” goes bust.

With so many suppliers failing recently, many people question why these insecure companies are allowed into the market. The short answer is that they drive prices down. I have personal experience of this, too. In 2017, I chose a really cheap supplier for my electricity. In 2018, they went bust. But for a year, I got the benefit of the reduced price. Do I wish that the failed company had never existed? No, I just wish I had found them sooner so that I could have taken advantage of their lower prices for longer.

Like many customers, I was in credit with the supplier at the point of failure. But none of us was left out of pocket. The new supplier always makes good the credit balance.

Obviously, someone has to pay. The cost of these credit balances is spread across all customers. It’s the equivalent of a financial insurance arrangement. Which is pretty much exactly what would happen if the system was re-designed in the way that critics call for. One possible change would be for the regulator to impose a capital requirement on all suppliers so as to reduce the likelihood that they will fail. Another approach would be for the regulator to require suppliers to enter into a cross-industry insurance arrangement. But both of these safety measures would cost money and the costs would still be spread across all customers.

There is one feature of the current system that probably could do with some improvement. Some of the failed suppliers had contracted in advance to buy energy at favourable prices. Those contracts lapse with the supplier who fails, rather than being passed on to the supplier who steps in for those customers. There should be an option – imposed by regulation or by statute – for the replacement supplier to pick up any of those contracts it chooses to. But there is certainly no need to throw out the current system in its entirety.

3 Price caps are not part of the problem

People who should know better have called for the price caps to be withdrawn. One former CEO of Centrica has argued as much. His central thesis seems to be that the price caps lead to “market failures of ill-equipped suppliers” without doing anything to overcome the massive increases in wholesale prices.

I don’t think I need to spell out why the failure of “ill-equipped” suppliers is not something to bemoan. The suggestion that price caps have failed in the face of turmoil on world markets is equally foolish, but the foolishness may not be so obvious.

Consumer price caps in the UK aren’t intended to control wholesale prices on world markets. They could never do that. And that’s not why the government introduced them. Competition in the UK market had done the job of bringing prices down for those who shopped around. But those who can’t shop around, or just didn’t bother to, were easy targets for suppliers who thought it a good idea to overcharge their loyal customers in order to cut prices for those with a keen eye for a deal. The current energy price caps were targeted very specifically at protecting those customers. Taking away that protection at this point would be a massive own goal.

We have seen something similar in the market for car and home insurance. The financial services regulator stepped in there, too. And so they should.

4 (Re-)nationalisation won’t help

There is something of a pattern in the first three myths. Each one of them tries to pull the wool over our eyes by making us think the position is something other than it truly is. The nationalisation myth is no different: there is no rational basis for the argument that the energy crisis demonstrates privatisation has failed.

We are asked to believe that nationalisation would do what exactly? Would putting energy companies under the control of the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy stop wholesale prices rising on world markets? As we search for ways to reach “net zero” emissions, would having the Secretary of State in charge of the energy industry lead to more effective means of production than we get from an industry fuelled by competition and innovation?

I am not someone who argues that the marketplace is perfect. It needs to operate in conjunction with regulators and a democratically-elected government. But it would be madness to think the current spike in energy prices is evidence that we need to dispose of the marketplace and the regulator, leaving the MPs in total control. We have been there before. It didn’t work.

5 The price cap is not what we are told it is

And so, finally, to the prices we read about in the news. They are very misleading. It’s a cheap point, but it needs to be made because it is symptomatic of the way the energy crisis is discussed.

A price cap is (fairly obviously) a maximum permitted charge. The energy regulator’s announcement last week, and most of the subsequent news coverage, described the cap as increasing by £693 pa from £1,277 to £1,971. But those figures aren’t the maximum. They are an average.

“An average of what?”, you may ask. They are an average of a hypothetical set of figures that almost certainly won’t be paid by anyone. Not even those who are “average”.

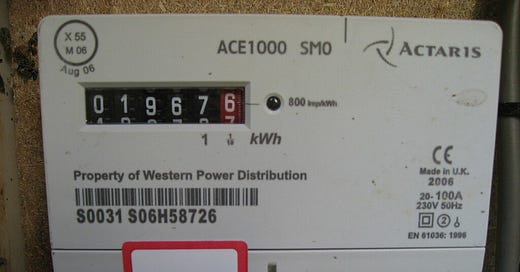

The actual price cap is set in pence per kilowatt-hour (kWh) plus a standing charge. The crucial figure – especially for those who face the terrible dilemma of heating vs eating – is the cost of switching on the gas, which is going to be 7p per kWh, up from 4p currently. (Full details for both gas and electricity are in a footnote below.[3]) But here’s the thing: this latest price cap starts in April and runs until September, a period of six months during which all the experts predict that it won’t be winter. Or autumn. The heating will be off.

By the time we next need to use our radiators in anger (or in fear), a new price cap will be in place. It may be higher than the current cap. Or lower. Given how volatile wholesale energy prices have been in recent months, we don’t know.

In other words, the £693 pa headline increase applies [helpful hint: take a deep breath and put a cold towel on your forhead] only if your consumption happens, quite coincidentally, to follow a pattern that equates to an average household using energy at prices that would have applied if prices turn out to be at a level that they almost certainly won’t be by the time when most of your consumption actually takes place. Got it?

This analysis reached you free of charge. Subscribe now to make sure you never miss any of my Irregular Thoughts. And share this particular thought with others so that they can read it.

[1] EU consumption is 36.66 billion cubic feet (Bcf) per day. Storage at the end of 2021 was 690 terawatt-hours (Twh). Applying the conversion rate from Twh to Bcf of 1:3.4, the storage level was 2,350 Bcf.

[2] UK consumption (at 2017 levels) is 2,795 billion cubic feet pa. The total EU storage is around 2,400 Bcf (see footnote 1).

[3] The gas price cap is going up from 4p to 7p per kWh and the standing charge is rising from 26p to 27p per day. The electricity price is going up from 21p to 28p per kWh and the standing charge is rising from 25p to 45p per day.