I try to keep these pages moving onto new topics. But sometimes events conspire against me.

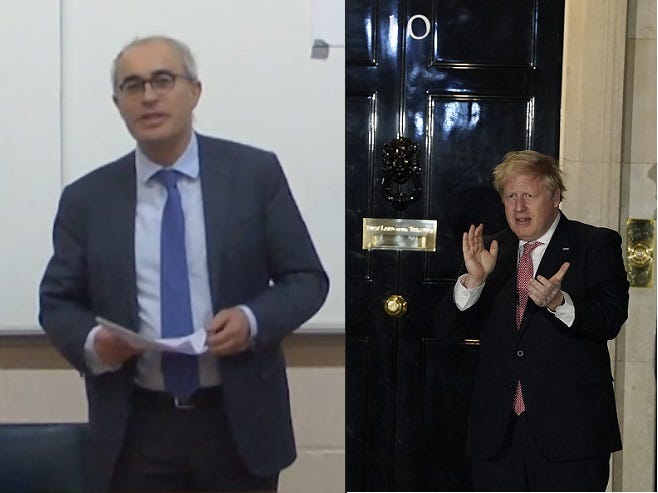

I have written about Prime Minister Boris Johnson and called him “a mendacious charlatan”. With his imminent fall from power, I had hoped not to need to write about him again.

In a completely different vein, I have also written a piece about Lord Pannick QC, in which I questioned the wisdom of his unsuccessful attempt to persuade the House of Lords to accept a proposition that I (and a majority in the Lords) found not very convincing at all. There should have been no need for me to write again about Lord Pannick for some while, if ever.

But, blow me down with a feather, Johnson and Pannick have teamed up in a way, and at a time, that I didn’t see coming. Perhaps no one did! It would be more than I could bear not to weigh in on the subject of this unexpected coupling. I don’t think you should blame me for doing so. I hope that some of you might even welcome it.

For those who missed the news, Boris Johnson asked David Pannick QC (along with fellow lawyer, Jason Pobjoy), to advise in relation to the inquiry conducted by the House of Commons Privileges Committee concerning statements Johnson made in the House which have subsequently been exposed as false. Johnson faces being found guilty of contempt of the House. Pannick and Pobjoy have issued their Opinion, which has been published on a Government website.

The Opinion kicks off with several succinct criticisms of the Committee, each of which the Opinion says will be expanded on in the detail. But are they? Take this criticism, for example: “The Committee has failed to recognise that a fair procedure requires that before Mr Johnson gives evidence, he should be told the detail of the case against him.” But the four paragraphs that the lawyers point to (paras 62-65) do nothing at all to substantiate any such failure by the Committee.

Of course, Johnson will know the case against him. He, and everyone else, knows it already. On close analysis, it seems that the lawyers’ point is actually that Mr Johnson should not be “required to give any evidence” until after all the evidence against him has been heard. In other words, once Mr Johnson has told the Committee anything at all, it would be “unfair” (to use his lawyers’ term) if the Committee is allowed to call a witness who could contradict what Johnson has said.

The Committee disagrees. But it has made it clear that, unlike in a court, Johnson would be allowed to give evidence more than once. His will even be the “final evidence” and he may get further opportunities during the Committee’s deliberations. Even that is not good enough for Johnson’s lawyers. They say that all the other witnesses should give their evidence ahead of Johnson. In other words, it is only fair that, once those witnesses have given their evidence, Johnson would be free to spin any lies he likes because no witnesses could subsequently be called to contradict him.

With procedures like that, Boris need have no fear. But he wants more.

The lawyers’ next five paragraphs (paras 66-70) are devoted to the argument that the lawyer who sits alongside Johnson to advise him during the hearings (which will be allowed) should also be allowed to speak on his behalf “to make any points of principle”.

In a court of law, that would be only normal and fair. Lawyers have three skills that are particularly relevant in a court. First, lawyers know the law, which lay people would not be expected to do. But this is not a court of law. It is a parliamentary procedure. The law doesn’t apply here. Parliamentary rules do. And Johnson is an MP.

Second, some lawyers are advocates; they can help to frame an argument which lay people may not be accomplished at doing. A bit like an MP or a journalist might do. Or a journalist who has become an MP. Or even a journalist who became an MP and then became Prime Minister, affording him hour upon hour of practice at responding to questions from other MPs. On what planet, exactly, is it unfair for someone like that to be left to their own devices when it comes to “mak[ing] any points of principle” to a Committee of MPs investigating a possible breach of parliamentary rules?

Lord Pannick gives an example from an occasion that he was personally involved in: the appearance of Kevin and Ian Maxwell in front of a House of Commons Committee in 1992. The Maxwell brothers were accompanied by three lawyers, one of whom made submissions to the Committee. A clear precedent in support of Pannick and Pobjoy’s Opinion? Not really.

The Maxwell brothers were not MPs. The issue was not one of parliamentary behaviour. The Maxwell issue concerned a massive criminal fraud. The brothers would, in due course, be charged with perpetrating the fraud, resulting in them appearing as defendants at a trial in the criminal courts (and found not guilty). It was those rights – the brothers’ legal rights – that the small army of lawyers had been hired to protect. And, of course, to address the Committee because the Committee could not be expected to know the criminal law. The Maxwell example is such a far cry from Johnson’s case that it is an utterly terrible argument.

Which brings me to the third skill that lawyers have. They can make a lousy argument seem plausible. Faced with an utterly worthless argument dripping from the lips of Boris Johnson, it is oh so easy for us to dismiss it. We’ve all had tons of practice. But the same argument issuing forth from the mouth of an eminent QC will inevitably carry more credibility even if it doesn’t deserve any.

The legal Opinion runs to 22 pages (over 7,000 words). The lion’s share is devoted to a debate over the Committee’s decision that it’s not necessary to prove that Johnson intended to mislead Parliament in order to find him guilty of contempt. It’s a tricky issue because an honest mistake should not be treated as contempt. And, of course, it isn’t. MPs frequently return to the House shortly after making a mistake in order to correct the record and are not investigated for contempt. More recently, ministers have been allowed to correct a mistake through a Written Ministerial Statement (used 200 times last year).

Johnson’s lawyers argue that the Committee should have to prove intent in order to find Johnson guilty. The House of Commons Clerk – someone who is an expert in parliamentary process – disagrees. She has advised the Committee that “ [i]t is for the Committee and the House to determine whether a contempt has occurred and the intention of the contemnor is not relevant to making that decision.”

The House of Commons is a special place with special rules. MPs are not allowed to lie to the House, but neither are they allowed to call out a lie by another member even when the lie is blatant and unarguable. Nor are words spoken in the House allowed to be tested in a court of law. The only place where lies in the House can be examined is through the procedure of a Committee such as the one that will review Johnson’s case

Boris Johnson has lied over and over again in the House of Commons and he used excuse after excuse to avoid correcting the record when it became clear that he had lied. But MPs have not been allowed to call out this behaviour in Parliament. Any attempt to do so leads to them being threatened with expulsion and, in some cases, actual expulsion. Calling out a lie is not prohibited in a court of law, but there can be no attempt to use the courts in relation to parliamentary matters because proceedings of the House are protected from examination by the courts.

So now, finally, Johnson is to face a hearing, in front of a House of Commons Committee using House of Commons rules, to investigate his deception in the House of Commons. And suddenly he wants all the normal protections of a legal process to apply … but without, of course, the threat of any legal sanctions.

I am not a Boris apologist (honest! - and I have not read the advice in detail) but…

I was under the impression that the key point of the advice was that if a PM can be censured for telling stuff to Parliament what he thought to be true at the time but which later turns out to be not the case then a dangerous precedent would be set. The implication being that a PM could not say anything that might be proved wrong in the future and that would massively curtail that PM’s ability to act in the moment.

I believe this is the central issue of “contempt” as set out in your piece.

I agree that the additional stuff – essentially about the inappropriateness of constraining the enquiry - has merit.

Whether Boris did think that the claims that he made were indeed true at the time is central to the case. I get a strong impression that your argument is that Boris lied so often that it is almost a statistical reality that this is just another lie in a long list of them. A view particularly appropriate for a qualified actuary. Of course proving this beyond reasonable doubt (as you would have to in a court of law) does depend on the confidence range used. There will aways be a chance ( albeit a small one ) that Boris did not lie in this case.

I must say holding future PMs to ransom in this way is not appropriate – although identifying bare faced liars is and there is merit in encouraging PMs to get their facts right in the first place. Indeed I resigned from the labour party (both in sorrow and disgust) a while back when it became clear that Blair’s dossier on WMD was not all it was cracked up to be.

Of course if he gets censured for telling parliament porky pies – which he knew were lies at the time – that is an entirely different matter.

My general view of Boris’ demise is that it is in many ways a true “Greek” tragedy. Funnily that is not to say it is necessarily “sad” – that depends on one’s viewpoint. The man did, in my opinion, get many of the big decisions right – he did get Brexit done ( well almost 😊), he did have the foresight to order massive doses of covid vaccine (notwithstanding other mistakes in this area) and he was/still is a strong rallying point for the West’s opposition to Putin’s special military operation.

He was ultimately undone by a fatal personal flaw which could be described as a lack of attention to detail in an area which although was undoubtedly hypocritical ( and worse) directly endangered only a small number of his inner circle – pretty much all of whom were complicit. Perhaps the greater crime was indeed lying about it in the subsequent (unsuccessful) cover up attempt.

I will bow to my more classically trained friends & acquaintances on this; however, I believe that this is the true definition of tragedy. A point undoubtedly recognised by Boris himself.